Introduction to JavaScript

A Brief History

In September 1995, when web browsers were in their infancy, Netscape programmer Brendan Eich was tasked with adding Scheme (a variant of the Lisp programming language) to the browser. However, his superiors wanted the language syntax to resemble Java.

In just 10 days (in order to meet the release schedule of the browser Navigator 2.0 Beta), Eich created a new programming language. It was initially named Mocha, then renamed LiveScript, and finally JavaScript.

Nowadays, JavaScript has been incorporated as one of the three core components of the web (the other two being HTML and CSS). JavaScript lives primarily in the browser, providing interactive functionality to what would otherwise be static web pages.

In addition to the browser, a relatively recent development is being able to run JavaScript on the server, using Node.js. With the creation of Node in 2009, JavaScript can now be used on the front end

and the back end of web applications. (And using Facebook's React Native, JavaScript can even be used for mobile development! JavaScript is truly everywhere.)

Getting Started with JavaScript

JavaScript is a fantastic language for beginner developers because it's very simple to get started. The base requirements for working with JavaScript is a reasonably up-to-date browser. That's it! (Although, having a code editor makes everything much easier, of course.)

Operators

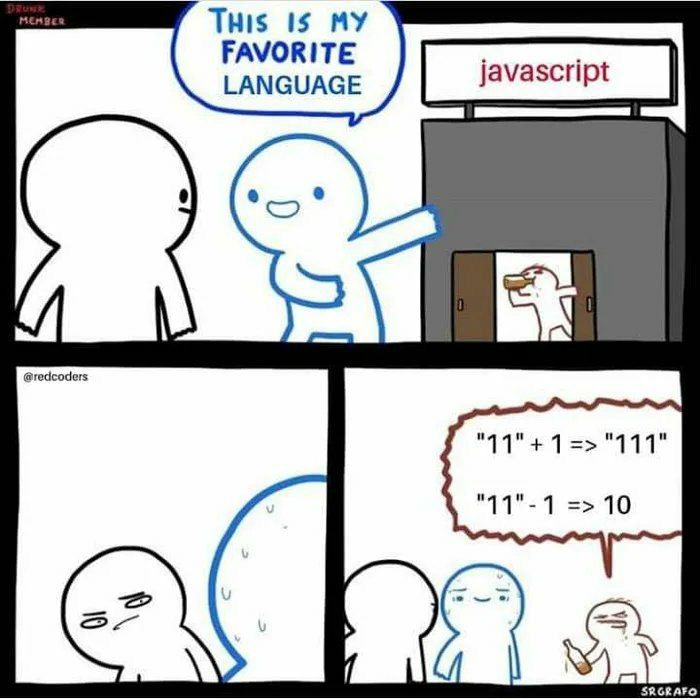

JavaScript, like most other languages, has some operators for doing arithmetic and assignment. It also allows using the

+ operator to concatenate (smush together) strings.

Arithmetic Operators

| Operator |

Name |

+ |

Addition |

- |

Subtraction |

* |

Multiplication |

** |

Exponentiation |

/ |

Division |

% |

Modulus (remainder) |

++ |

Increment |

-- |

Decrement |

Logical Operators

| Operator |

Name |

&& |

AND |

|| |

OR |

! |

NOT |

Equality Operators

| Operator |

Example |

== |

Equality operator |

=== |

Strict equality operator |

!= |

Inequality operator |

!== |

Strict inequality operator |

< |

Less than operator |

> |

Greater than operator |

<= |

Less than or equal to operator |

>= |

Greater than or equal to operator |

An important note…

=>

is

not an operator. It is the notation for

arrow functions.

JavaScript is also interesting in that it has

two equality operators, regular and strict. Simply put, the regular equality operator _allows type coersion_ and the strict equality operator does not. That is,

1 == "1"

will evaluate to

true when using the regular equality operator, because the string will be coerced into a type of number:

1 == 1

and then compared.

The same statement will evaluate to

false when using the strict equality operator, because JavaScript will not perform coercion, and will instead compare the number to the string:

1 === "1"

This can be a useful feature whenever you want to make sure you're only comparing apples to apples. However, the regular equality operator has its uses as well, for instance when you may

want to compare coercions (such as when returning results from a web form). While there is much fuss in the JavaScript community about how you should "only use strict equality," as with any other language feature, as long as you're aware of the consequences of your choice, either equality operator can be useful.

Assignment Operators

| Operator |

Example |

Syntactic Sugar For |

= |

x = y |

x = y |

+= |

x += y |

x = x + y |

-= |

x -= y |

x = x - y |

*= |

x *= y |

x = x * y |

/= |

x /= y |

x = x / y |

%= |

x %= y |

x = x % y |

**= |

x **= y |

x = x ** y |

JavaScript offers what's known as

syntactic sugar for its assignment operators. Syntactic sugar just refers to any shorter and cleaner syntax option. It comes from the idea of sprinkling sugar on something to make it sweeter and more appetizing.

For the assignment operators, JavaScript provides a shorter syntax for performing an operation when assigning something, which can save a little bit of code and can often make the steps performed in the code a little bit more obvious.

String Operators (for Concatenation)

| Operator |

Example |

+ |

let a = "String 1" + " " + "String 2"

console.log(a) // "String 1 String 2" |

+= |

let a = "String 1"

a += " String 2"

console.log(a) // "String 1 String 2" |

In JavaScript, the concatenation symbol is the same as the addition symbol. As expected in a loosely typed language that allows for silent coersion, this can lead to some issues (such as the infamous

"11" + 1 = 111

"11" - 1 = 10

problem…

Data Types and Structures

If you're familiar with other programming languages, especially strongly typed languages like Java, you might be well acquainted with types. Unlike those languages, which are

strictly typed, JavaScript is

loosely typed and sometimes called

untyped.

What this means is when you declare a variable in JavaScript, you don't need to declare a type:

let a = 10. In a strictly typed language like Java, you would need to declare

int x = 10 to tell Java that your variable is an integer. JavaScript, on the other hand, will happily infer the type for you. This can sometimes lead to some unexpected errors, because JavaScript can allow types to be inferred as other types (called

coercion), and this might not be what you expect. (For instance,

1 + '2' becomes

'12' instead of

3 like you might anticipate.)

JavaScript is also

dynamically typed, which means that the types of variables can

change and be reassigned. For instance, this is perfectly valid:

let a

a = 10

typeof a //"integer"

a = "ten"

typeof a //"string"

a = [10, "ten"]

typeof a //"object"

This means that you can be really flexible with the programs you write. However, it also means that it's easier to overwrite a variable you didn't intend to.

Primitive Types

A

primitive is data that is not an

object and has no methods (functions) attached to it. There are six primitive types in JavaScript. They are:

- undefined

- Boolean

- Number

- String

- BigInt

- Symbol

There is also one special case that is technically a primitive but has some caveats attached (see below):

undefined

let a = undefined

typeof a === "undefined"

Undefined is a special value that indicates your variable has been declared, but has no value. (You'll mostly see this in debugging, because if you want to declare a variable and set it to an empty value immediately, it's best to set it to

null, not

undefined.)

Boolean

let a = true

typeof a === "boolean"

A boolean is what it sounds like; it can be set to either

true or

false.

Number

let a = 5

typeof a === "number"

A number in JavaScript can either be an integer (no decimal point) or a floating-point (with decimals). JavaScript makes no distinction between the two. While this makes calculations with numbers more convenient, due to the way JavaScript stores numbers in system memory, it also makes them prone to rounding errors. (Try putting in

0.1 + 0.2 into the console of your browser and see what you get.) Also due to the way JavaScript works with numbers, the largest value the Number type can handle is 9,007,199,254,740,991 (which, if you ever need it for some reason, can be accessed by the Number property Number.MAX_SAFE_INTEGER).

In ES2020 (the version of JavaScript released in 2020), BigInts were introduced to handle numbers larger than Number.MAX_SAFE_INTEGER). They come with their own caveats noted below, and it should be noted that you can't mix Numbers with BigInts without converting one to the other first (ie

1n + 6 is invalid).

There is a special "number" in JavaScript --

NaN, which stands for Not a Number. (If you enter

typeof(NaN) in the console, you will get

"number", despite the fact that it is, quite literally,

not a number.)

NaN will crop up if you attempt to do mathematics with strings, like

100 / "Apple". If you do multiple calculations in a row and NaN is introduced somewhere along the line, all subsequent values will become

NaN as well.

There is another special number in JavaScript,

Infinity. It is what it says on the tin, and can either be positive or negative.

JavaScript also has several other number-related features -- it can perform operations in hexadecimal, octal, and binary. (For this reason, never write numbers with a leading

0 -- some older implementations of JavaScript will interpret these numbers as octals.)

String

let a = "5"

typeof a === "string"

A string is a series of characters. JavaScript supports using either single quotes:

'I am a string.' or double quotes:

"I am also a string."

As of version ES6, JavaScript also supports what are known as

string literals -- very useful strings enclosed with backticks, which can support including variables without leaving the string:

`I am a string literal, which contains a ${variable}!` String literals also allow for spacing across multiple lines without needing to use special non-printing characters in your string like

\n (which represents a *n*ew line). For example:

`This

string

will span

multiple lines.`

If you don't use a string literal but need to include a variable, you will need to

concatinate your string with your variable:

"I am a plain old string with a " + variable + "!" If you want to span multiple lines with a regular string, you need to use non-printing characters like

\n, which will add a new line.

"This\nstring\nwill also span\n multiple lines\nbut it doesn't look as nice as a string literal!"

Strings in JavaScript are

zero-based, which means that like arrays, the first character is considered position 0, the second character is position 1, etc.

BigInt

let a = 1n

typeof a === "bigint"

BigInts are the new way of working with extremely large numbers in JavaScript. They are denoted with an

n following an integer (BigInts cannot deal with decimals). You can't mix BigInts and Numbers, but assuming the other rules are met (ie the number is not too large if going from a BigInt to Number, or the number doesn't have decimal places if going from Number to BigInt), you can convert BigInts to Numbers and vice-versa.

BigInt(123) converts the Number

123 to the BigInt

123n.

It should be noted that the "n" is simply used to denote that the number is a BigInt; it has no special meaning otherwise. (ie a BigInt of 1n is technically the same "size" as a Number of 1.)

Symbol

let a = Symbol()

typeof a === "symbol"

Symbols were introduced in ES6. No two Symbols can equal each other, that is…

Symbol() === Symbol()

…will return

false.

Their use case is a little advanced, but essentially they provide a way to prevent

name clashes, where two properties have the same name. Symbols are used as part of a

factory function (a function that creates many copies of objects, hence

factory), and ensure that each property name on the objects they make is unique.

null

let a = null

typeof a === "object"

That's not a typo --

typeof a is an object. It

should be typeof a

= null. This is a bug that's existed since JavaScript was created, and will almost certainly never be fixed. (If you're curious, here's an explanation of exactly why this occurs that digs into JavaScript's underlying C code:

typeof null: investigating a classic JavaScript bug.

null in JavaScript represents

nothing, a missing, empty value.

Structural Types

You might hear the joke that everything in JavaScript is an object.

This isn't too far off from the truth! Except for the primitives listed above, everything in JavaScript

is an object. Where primitives store only one value, objects of all types can be more complex and store many values. Objects can have

methods, or functions, attached to them, whereas primitives cannot.

There are two important takeaways to remember about the distinction between primitives and objects:

- Primitives cannot have methods, only properties; objects can have methods and properties

- Primitives are referenced by value, whereas objects are referenced by memory location

Take note of that last point. What this means is

let a = "a string"

let b = "a string"

console.log(a === b)

will evaluate to

true.

However, if we simply turn these primitives into objects…

let a = ["a string"]

let b = ["a string"]

console.log(a === b)

This code will evaluate to

false. Now that these are objects (Arrays), JavaScript is no longer comparing the

content of the strings, but instead it's asking whether

a and

b are

literally the same object occupying the same location in memory. This can easily trip you up when coding, so it's important to keep in mind!

There are two main "divisions" of objects in JavaScript: functions, and everything else.

Functions

function helloWorld() {

console.log("Hello world!")

}

Functions in JavaScript look very similar to most other programming languages. They are blocks of code designed to perform a specific task.

Every function must be declared with the

function keyword. The parentheses after the function name contain the

arguments, if there are any. Functions are generally split into

function declarations and

function expressions. A function

declaration starts with the word function, whereas a function

expression is part of a variable expression:

// Function declaration:

function helloWorld() {

console.log("Hello world!")

}

// Function expression:

let helloWorld = function() {

console.log("Hello world!")

}

Function

expressions can be either named or

anonymous, as in the case above where the function itself does not have a name. You will most likely see mostly anonymous function expressions in actual code.

There are also special use-cases you might occasionally see called IIFEs,

Immediately-Invoked Function Expressions:

(function helloWorld() {

console.log("Hello world!")

})()

This code calls itself and will run immediately.

Finally, you may also see a relatively new addition to JavaScript,

arrow functions. Without getting deep into the meaning of

this in JavaScript (an enormous topic), essentially arrow functions provide a shorter syntax for declaring functions:

// Old way:

let helloWorld = function() {

return "Hello world!"

}

// New way with arrow functions:

let hello = () => {

return "Hello world!"

}

// If the arrow function has only one statement, you can remove the curly braces and any return statement as well:

let hello = () => "Hello world!"

Arrow functions are useful because they don't bind

this.

this is a special keyword that normally represents the

object that calls the function, which might be the window, the button, etc. In arrow functions,

this represents the object that

defines the arrow function. (

this is a very difficult concept to grasp for even experienced programmers, so don't worry if it doesn't make a whole lot of sense.)

Every function in JavaScript must return a value. If you don't explicitly tell the function to return something using the

return statement at the end of the function, the function will return

undefined. (This is perfectly acceptable; sometimes you don't need a function to return anything.) Any code that comes after a

return statement at the end of a function is ignored.

Objects

//An array:

let cake = ["eggs", "milk", "flour", "sugar"]

//An object:

let person = {firstName: "Troy", lastName: "Baker", age:44}

Arrays and Objects are the most well-known objects. Objects also include

Maps,

Sets,

WeakMaps,

WeakSets,

Dates and anything declared with

new (including primitives if you declare them in this way!).

Arrays are

zero-indexed, which means the first item in the array is item [0]. Arrays can hold any variable type in them, and you can mix variable types within arrays. (

["a", 2, variableName] is valid.) Array elements are separated by commas.

Objects are

key-value pairs. This means that for every property on the object, there's a corresponding string that identifies it. Properties are invoked using the identifying string. Importantly, objects in JavaScript are compared by

reference, not by

content (see the

Structural Types section for an overview).

Objects have two ways of being created: object construction (

let a = new Object()) and object literal (

let a = {"key": value}). Most people use the object literal form. There are a few differences between the two methods, but it's generally for more advanced use-cases, and not as helpful when you're just getting started with JavaScript. (Objects defined using the constructor method will allow multiple

instances of the object, so that making a change to one instance will not affect other instances of that same object.)

Variables

JavaScript allows several different ways to declare variables, which might be surprising if you have been working with most other languages. There are three different keywords to create a variable:

var,

let, and

const.

Variables in JavaScript must have unique names. (Variable names don't have to be unique to the program, but they must be unique within the

current scope. See the section below on

Variable Scope.)

Variables:

- Can contain numbers (though they must begin with a letter)

- Can begin with, and contain, underscores and dollar signs

- Are case sensitive

- Cannot be a reserved word in JavaScript (like

let, function, final, private, etc)

Variables are

assigned with the equals sign operator.

Var

Before 2015 (and the release of ES6),

var was the only way to declare a variable in JavaScript.

var is

function scoped, which means that if the variable is declared within a function, it can be used anywhere within that function. (This can be very problematic for variables declared within, say, for loops, where you don't want the rest of the function outside of the for loop to have "knowledge" of that variable!)

As a general rule,

var is considered to be outdated. If you can use one of the other two types of variable declaration keywords (

let or

const), you should. You may not be able to do that if you need to support older browsers or are working with older code, however.

Let

For any code that doesn't need to support older browsers (pre-2015),

let should generally be used anywhere you would have previously used

var. Unlike

var,

let and

const are both

block scoped, which means that they are

only available within the local scope.

Scoping is a difficult concept to understand as a beginner. A good basis is

the w3 tutorial on let. Essentially,

let and

const are less available to the rest of the program than a variable declared with

var. This is a good thing: the worst thing a program can have is lots of global variables cluttering up the code. This can easily lead to unexpected results and difficult to track down errors.

Const

const is similar to

let in that it is block scoped. However, the big difference between the two is that

const cannot be reassigned.

const is short for

constant, and should be used whenever you have a value in the program that will not change. This makes it useful for any variables in your program that should keep their value and not be altered (intentionally or unintentionally).

Variable Scope

Variable scope is a big topic, and can be difficult for beginners to understand. I would recommend starting with a good overview of the subject, like

this overview of scope and hoisting (although this tutorial was created before

let and

const came on the scene).

Essentially, every variable has its own

scope. Scope refers to the parts of the program that have access to your variable. Different variable declaration keywords, as described above, will result in different scopes for your variable (with

var being function scoped and

let and

const being block scoped). In a nutshell, you want the smallest scope possible for your variables, which is why

let and

const are better choices for modern programming.

JavaScript also has an interesting feature related to scope called

hoisting (which that tutorial also covers). It's a bit of an advanced subject, but hoisting a variable essentially means that at runtime, JavaScript splits this statement:

let apple = "red"

up into two parts, the declaration:

let apple

and the assignment:

apple = "red"

and then moves the

declaration up to the top of the variable's scope. (This also happens with function declarations.) This isn't something that can be controlled by the programmer, it's just a normal part of how JavaScript works.

All the beginner needs to take away from this, is that as a general rule, it's best to declare all your variables as close to the top of the scope they'll be used in as possible (which generally means at the beginning of each function).

If/Else

Like most other languages, JavaScript has conditional statements to control the flow of your program (see the Truthy and Falsy section below). The syntax is fairly simple:

if (variable > 0) {

// If the variable is greater than 0, do this code

} else {

// If the variable is less than 0, do this code

}

The

if statement takes a variable and a comparison, and coerces that statement into a boolean ("is the variable greater than 0? true/false") and then it will run the appropriate code.

Truthy and Falsy

JavaScript values can be either

truthy or

falsy. A truthy value is one that is considered to be true when made into a boolean (such as when evaluating an if/else statement), and a falsy value is one considered to be false when made into a boolean.

In JavaScript,

all values are truthy unless they are one of the following:

-

false

-

0

-

-0

-

0n

-

""

-

null

-

undefined

-

NaN

All of the above values will evaluate falsy.

The Ternary Operator

JavaScript also has a neat little feature called the

ternary operator. This is essentially a shorthand way of writing a simple if/else statement that assigns a value to a variable that can save a bit of coding. It works like this:

let result = (variable < 0) ? "True" : "False"

The first part, the parentheses, takes a statement to evaluate that you would normally put after an

if. That is followed by a question mark (the ternary operator). If the statement resolves to true, it will return the first value (the string

"True" in this case). If it is false, it will return the value found after the colon (the string

"False" in this case).

You can essentially look at it as if it's asking a question: is this statement true? If yes, assign the first part of the statement to the variable. If no, assign the second.

This can be a little bit difficult for beginners to grasp, so here is another example. Let's say someone is allowed to vote, but only if they are over the age of 18:

let age = 18;

let canVote = (age >= 18) ? 'Yes' : 'No'

This same code could be written this way:

let age = 18;

let canVote;

if (age >= 18) {

canVote = "Yes";

} else {

canVote = "No";

}

Switch Statements

In an effort to be more friendly to people coming from other languages like C, JavaScript also recently implemented support for

switch statements. These are useful where you would otherwise have long, nested if/else statements.

The syntax looks like this:

switch (expression) {

case firstChoice:

// if the first case is true, this code gets run

break;

case secondChoice:

// if the second case is true, this code gets run

break;

default:

// if none of the cases run, this code gets run

}

The

default section is optional, and can be omitted if there's no chance that at least one of your cases won't run. You can have as many cases as is necessary. Check out

the developer guide to switch statements for more in-depth information and some more examples.

For Loops and While Loops

There are several kinds of loops in JavaScript:

- for loops

- for…in loops

- for…of loops

- while loops

- do…while loops

For Loops

The basic for loop has a pretty simple syntax. The statement in parentheses is broken up into three smaller statements: first, you declare the variable used for incrementing. Second, you declare when to stop the loop. Third, you declare how much the variable will increment after each loop.

text = "";

for (i = 0; i <= 10; i++) {

text += "The number is currently " + i + "\n";

console.log(text);

}

In this loop, the counter (traditionally,

i is used as a loop counter variable) is initialized as

0. Then, we tell the loop we want it to stop when

i reaches 10. Then every time we go through the loop, we want to increase the value of

i by one.

For each loop, the console will print out the statement "The number is currently" and the current number. (The

\n represents a line break, so that it's more easily readable.)

(As a footnote, the third part of the statement (where you increment the variable) is actually optional. You can increment the variable inside of the loop if you wish and leave that out altogether from the loop construction. However, most people don't do this, so it could be less readable. And of course, if you forget to increment inside the loop instead, you'll end up with an infinite loop!)

For…in Loops

For…in loops are for loops explicitly for looping through the

properties of an object.

for (variable in object) {

// code goes here

}

For…of Loops

For…of loops are for loops explicitly for looping through the _values_ of an iterable object (such as arrays, strings, Maps, etc).

for (variable of iterableObject) {

// code goes here

}

While Loops

While loops are similar to for loops, but have some notable differences. While a for loop will run until some condition

is met, a while loop will run until some condition

is not met.

They're a lot simpler to construct than a for loop. You simply plug in a condition, and make sure there is something in the body of the loop that will eventually make that condition not true so that the loop can end.

while (condition) {

// code goes here -- don't forget to include something that will break the loop eventually!

}

Do…while Loops

The do…while loop is a variant of the while loop. This loop will always execute

once, no matter what, and will then check if the condition is true after its first execution. Then the loop will repeat as long as the condition is true.

do {

// code to execute

}

while (condition);

Strict Mode

Strict mode was a new feature released in ECMAScript 5. Strict mode is an attempt to enforce some previously lax rules that will turn bad syntax into actual errors.

If you turn on strict mode in your code, there are a few changes:

- You cannot use undeclared variables. Without using strict mode, if you use a variable without declaring it first (either by not noticing it was not declared, or perhaps by making a typo in an existing variable name), JavaScript will "helpfully" turn this new variable into a global variable for you. This can cause all kinds of unintended errors. This is not possible with strict mode turned on.

- You cannot use undeclared objects either.

- You cannot assign something to a non-writable property, a getter-only property, a non-existing property, a non-existing variable, or non-existing object.

- You cannot delete an object or variable.

- You cannot delete a function.

- You cannot delete an undeletable property of an object (like

Object.prototype).

- You cannot duplicate a parameter name (for example

function x(length, width, length) {})

- You cannot use octal numeric literals (for example,

x = 010)

- You cannot use octal escape characters (for example,

x = '\010')

- You cannot use

eval or arguments as a variable name.

- You cannot use the

with statement.

- You cannot use

eval() (which is very important for security reasons!)

-

this behaves a little differently. this refers to the object that that calls the function. In non-strict mode, if that object is not specified, this refers to the global object (usually but not always the browser window object). In strict mode, it returns undefined.

You enable strict mode by putting

"use strict" at the beginning of your code. This will enable it globally. (It is also possible to put

"use strict" inside of a function, at the top, which will enable strict mode for that function only, however this is not as common.)

Semicolons

One quirk of the language that you may have noticed is that while some coders will place semicolons at the end of their JavaScript lines, others may not. This is because JavaScript has something called

automatic semicolon insertion. It's exactly what it sounds like: at the end of each line, behind the scenes, if you haven't put a semicolon at the end of each line, JavaScript will automatically insert it when the code runs.

There are a few rules to keep in mind if you

don't want to use semicolons in your code, and want to allow JavaScript to insert them automatically. JavaScript will insert semicolons in the following places:

1. When the next line starts with code that breaks up the current code (that is, if JavaScript

can continue reading your code without getting confused, it will add a semicolon only after it can't parse anymore)

2. When the next line starts with a closing

} bracket

3. When the end of the code is reached

4. When there is a

return statement on its own line

5. When there is a

break,

throw, or

continue statement on its own line

Classes (vs Prototypes)

Another relatively recent addition to JavaScript is the syntactic sugar of classes. Before explaining exactly what these are, it's important to get a little background knowledge.

JavaScript is a

prototypal language.

You Don't Know JS has an

excellent explanation of what this means, but essentially, every object in JavaScript has a private property which links to another object, the

prototype. That's right: nearly every object you make will in actuality be an instance of

Object!

When new objects are constructed, they become inherently linked to each other on what's called the

prototype chain. If JavaScript is looking for a property that your code says should be found on your object, and it doesn't find it on your object, it will continue climbing up the prototype chain until it either finds the property or throws an error. For those familiar with computer science terminology, the prototype chain is essentially a

linked list (and yes, at the end of the list is

null).

This is a very powerful model! But it can also be very confusing for people coming from languages that use class-based syntax. So in ES2015, JavaScript introduced the syntactic sugar of JavaScript classes. (Underneath the hood, JavaScript is, and will always be, a prototypal language, but the class syntax can be especially helpful for those that prefer the class-based model.)

In JavaScript, classes are declared like so:

class ClassName {

constructor() {

// code goes here

}

}

The constructor is a special method. It

must use the name "constructor." It is executed automatically whenever a new object is made, and will initialize the new object's properties. (If you forget to include a constructor, JavaScript will create an empty one for you.)

Other Resources

--

SelenaHunter - 01 Feb 2021

Create New Topic

Create New Topic

Index

Index

Search

Search

Changes

Changes

Notifications

Notifications

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

Statistics

Statistics

Preferences

Preferences

Automation

Automation

Main

Main

System

System

Testing

Testing